Kindness Amidst the Conflict

Jerry Gore, a passionate climber and humanitarian, shares his experiences during a harrowing journey cycling from London to Kyiv to raise awareness and funds for children with T1D (Type 1 Diabetes) living in war-torn Ukraine. He sheds light on the impact of the Ukraine war while inspiring kindness and compassion along the way.

Text and photos

Jerry GORE

PARTICIPANT

Paul BUCKLEY

As Paul and I cycled away from the Prime Meridian in London’s Greenwich Park, I reflected on what we were just about to do – a 3,000Km cycle ride from the safety of western Europe to war-torn Kyiv in the middle of Ukraine. The Prime Meridian represents global unity and human connection across time zones and countries. In a nutshell, that was our mission: to unite the European cycling and diabetes communities and bring a message of hope and solidarity to those Ukrainians who shared the same chronic health condition as I did — T1D (Type 1 Diabetes). We also wanted to raise money to buy specialist diabetes equipment for displaced T1D children across the country.

I had started planning the logistics and organisation back in January 2023. It was now the 26th of August 2023, one and a half years since the illegal Russian invasion. I had heard from many sources that the country was now a shadowed realm, torn apart by incessant bombing, day and night. Would we experience the realities of this stricken country, or fail to even reach its borders? I looked across at Paul and smiled nervously.

I had only met this giant of a man once, just for 30 minutes at a barbecue in the Southern Alps. Neither of us had cycled anything even close to this distance before. Would we survive, would our friendship endure, and would we make it to Kyiv together? Would our ride make any difference to anyone, and would my diabetes condition affect me and prevent me from continuing? Paul smiled back and we pushed our pedals on the first day of what turned out to be an epic adventure.

Every year since 2003 I have undertaken what I call a JIC — Jerry’s Insulin Challenge — to raise money for impoverished children with Type 1 Diabetes. But 2023 was different. I had tracked and followed the war in Ukraine ever since the start and it had really got under my skin. I had to do something. So, in 2023 I changed tack a little and RideUkraine 2023 was the result. Whether it’s divorce, disease, family disasters or war, I feel only real pain and sorrow for the children affected. They have no defence, no experience and no understanding to be able to cope with suffering and hardship. I could only guess at the level of fear and anxiety an eight-year-old child with T1D would feel in the midst of this illegal and terrifying invasion. I would soon find out.

The Route

I planned the route to be as direct as possible across Europe, based around the EuroVelo 4 cycle path — The Central Europe Route. We would cycle back roads to Dover, take the ferry to Dunkirk, and then cycle through France into Belgium, up to Eindhoven in Holland and straight across Germany to Dresden. From there we would drop into Czechia to Prague and continue west. At Ostrava we would cross into Southern Poland and then continue east to the Ukraine border. In Lviv we would meet our Ukrainian cycling guide Alex and our Ukrainian co-lead Dr. Iryna Vlasenko. From Lviv it would be another 700Km to Kyiv.

For accommodation, I chose an assortment of options — Booking.com, Airbnb, WarmShowers, local friends and members of the European division of The International Diabetes Federation. I planned the route using Strava and downloaded each day onto my Wahoo Roam 2. I would book accommodation as we cycled, two nights in advance, and once we arrived in the vicinity, Paul would navigate the last portion using Google Maps.

JERRY GORE

I had never ridden further than 360Km before. But I just felt that for RideUkraine I wanted to ride like I usually do, relatively fast and light, averaging between 120Km and 180Km a day. I chose my beloved Giant Defy Advanced Pro 1 — or TGM (The Green Machine) as I called her, an endurance carbon road bike built for long days on tarmac. I had no way of knowing how bad the roads would be in Ukraine, but I chose speed and lightness over strength and reliability, banking on fast smooth road surfaces.

Paul Buckley

I live in the Southern Alps, and by pure chance at a dinner in early June that year, I sat next to Paul. I had never met him before, and we started to chat about our lives. Paul was a maintenance man, great at anything practical like plumbing, mechanics and electronics. He had only ever cycled short distances for fun, had never done any bikepacking adventures, had not travelled much, had never been to Eastern Europe, and spoke just one language. And that was very definitely English!

In contrast, I am a businessman and a former UK military officer who moved to the Southern French Alps in 2003 after my T1D diagnosis. I’ve travelled extensively on numerous climbing expeditions since the late 1970s, speak several languages, and have dual French and British nationality. Paul and I were VERY different, but we didn’t know that then. Everything comes out on a long-distance bikepacking adventure!

We were riding into a war zone, so I decided we should be well prepared. Another top tip is to carry only spares you know how to install and use. I carried a light bike maintenance kit, while Paul carried a more comprehensive set including gear and brake cables, a rear derailleur hanger, chain quicklinks, and spare brake pads. We also carried medical supplies including tourniquets and “Israeli bandages” designed to stop haemorrhaging wounds. I had to carry all my insulin, needles, and blood-sugar testing kit. My “luxury” item was Specialized’s best long-distance road bike saddle. Paul’s was two pints of beer every night!

I had been planning the logistics since January 2023. Paul confirmed his participation in early July, buying a second-hand bike for €480 and second-hand panniers. He had just 3 weeks to train, doing 50Km circuits three times a week. It was a gamble we would only know we had won when we reached Kyiv.

The Journey Begins

The first stage was London to Dover, about 150Km using back roads. It rained incessantly throughout! We had about 30 volunteers, friends and family to see us off. Just 20 minutes after leaving Greenwich we passed a horrendous car accident, a salient reminder of what potentially lay ahead.

The great news was that a cohesive organizing committee for RideUkraine had formed, proving essential as they generated thousands of followers on social media and a lot of support on our ride across Europe. I had tried various contacts without success but eventually found the perfect lead co-ordinator – Dr. Iryna Vlasenko, a Ukrainian with T1D and Vice President of IDF (The International Diabetes Federation). She immediately understood our mission and helped coordinate with partners including Direct Relief and IDF Europe.

After our triumphant departure from London, we arrived in Dover soaked, tired, and with a strong sense of loneliness as it was just Paul and I from now on. But our adventure had truly begun. The ferry to Dunkirk was fast and easy, and we were soon onto sandy trails along the French section of the EuroVelo Maritime Coast route. Within two days we were in Holland heading west for Germany, loving the peace, calm and security of the endless cycle paths. Although we were averaging 140Km a day, Paul was suffering badly.

Weighing 114Kg, Paul didn’t have the ideal build for long-distance endurance events. He struggled manfully with few complaints, but his low-cost bike setup started causing problems. In Holland, the sole of Paul’s shoe fell off. We found a local bike shop where the owners treated us with remarkable hospitality, inviting us into their huge premises, telling us to “put your bikes anywhere,” and serving us free coffee.

Challenges Along the Way

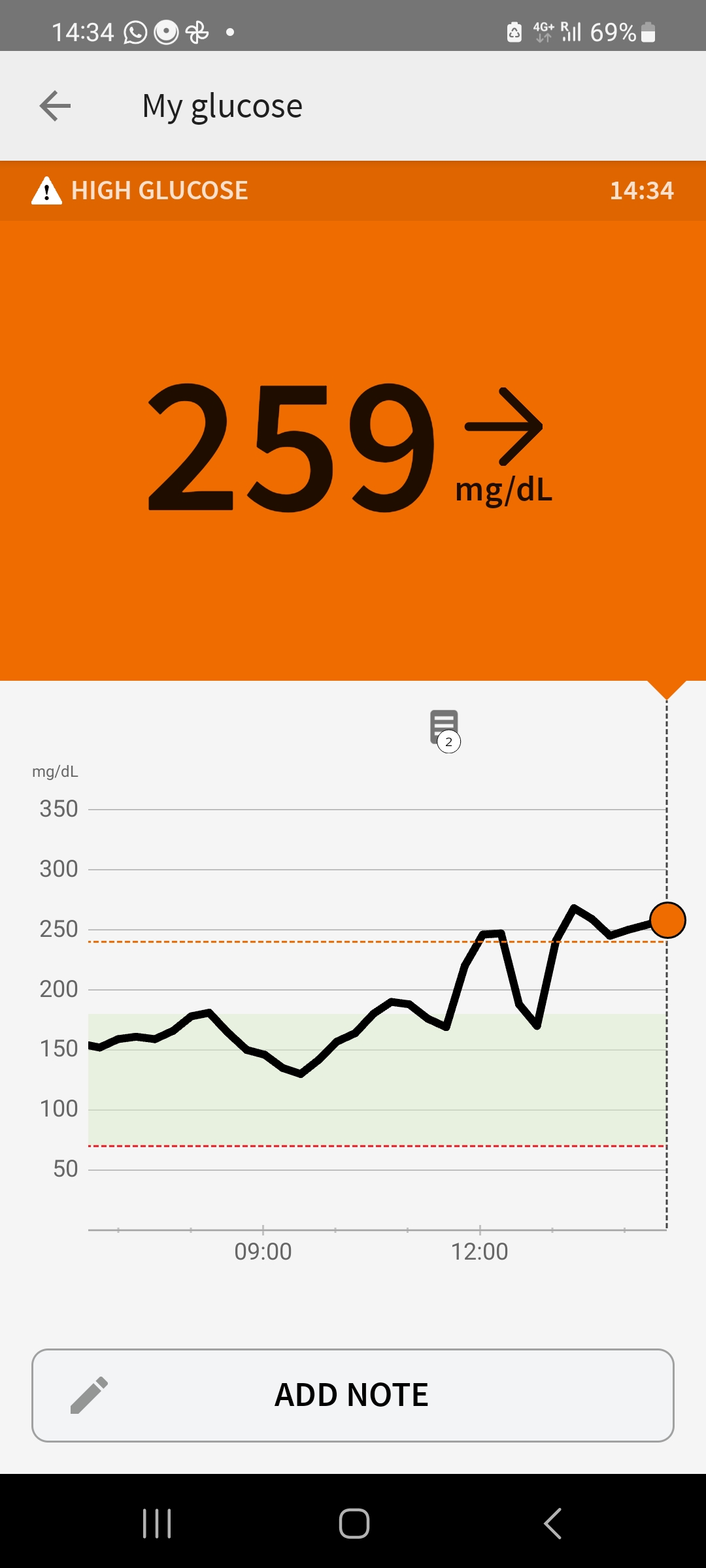

One of the daily issues was my hypoglycaemic attacks. Being a T1D, I suffer from high and low sugar levels. Counting carbohydrates is impossible on a bikepack when every meal is different, and we were consuming up to 5,000 calories a day. Every day I had to guess how much insulin I needed, and riding long distances made me super insulin sensitive, so just one tiny drop too much might cause a hypoglycaemic attack within an hour.

To counter each hypo, I needed to consume fast-acting carbs – drinks like Coca-Cola or foodstuffs like honey or candy bars. It’s a constant balance that could make me very grumpy at times. Paul had never dealt with T1Ds before, and now he faced one 24/7 during a long-distance endurance event. Beer was our nightly solution, and often we collapsed onto our beds happy, but absolutely shattered from the day’s emotional and physical demands.

In Ghent, Belgium, we had both great and awful experiences. We met a team of T1D cyclists from our IDF Europe connections, including a 12-year-old boy with T1D. We rode together for a few hours, sharing stories and feeling the camaraderie and solidarity. The boy’s father thanked me warmly for inspiring his son. What wasn’t beautiful was when Paul got his wheels caught in tram lines and fell off.

Paul was badly bruised but thankfully nothing was broken.

Sadly, soon after this he had his first puncture, and this continued every day for the next 2 weeks, averaging 2-3 punctures daily. Each time Paul would repair without complaint whatever broke on his bike – panniers, punctures, shoe cleats – but I wasn’t happy to enter Ukraine knowing we might have to regularly stop for repairs. Finally, the problem was diagnosed by a bike shop in Rzeszów, Poland: bad rim taping on Paul’s wheels was causing pressure on the spokes, routinely splitting his inner tubes from the inside.

Deeper Into Europe

Just after Essen in Germany, we experienced how divided Germany is regarding the Russian invasion. In Duisburg, a pedestrian shouted, “I don’t like fascists!” at us. “Neither do I!” I shouted back. Later, another pedestrian tried to force Paul into a barrier at 25km/h.

The section from Neheim to Kassel in central Germany was tough. It rained all day! We hit a nasty 10km section of gravel in pouring rain, which damaged our disc brakes. After 10 hours of cycling in heavy rain, we couldn’t reach our destination, and I had to search for new accommodation while soaked and very cold. Finally, I found a lodge that was still open with a spare bed and couch. Heaven!

The next day didn’t start well either. My blood sugar went down straight after breakfast because I mistakenly injected too much insulin so now on a full breakfast stomach, I had to start eating again. As my blood sugars dropped, so did my mood. I started arguing with Paul, and soon I was too weak to keep up with him and he faded into the distance. I stopped in the middle of a forest section. I just ate two cereal bars and felt angry. Paul phoned me and asked me where I was. Eventually my sugars rose, and I caught up with him. We found a coffee shop soon after, sat down and talked it through. I apologised for having the hypo and being so argumentative. He understood completely. We hugged and went to a supermarket. I restocked on cereal bars, and we cycled on.

Eventually after leaving the beautiful city of Dresden, we crossed the border into the Czech Republic and shortly arrived in Prague. All my family on my mother’s side were born and raised in this amazing city, and all were destroyed during WW2. Nazis then Russians took care of that.

In Prague, I woke up with a sore back and searched for a massage therapist. Through a complex series of interactions, I ended up meeting a Ukrainian woman and her 21-year-old daughter Julia. When I mentioned we were cycling to Ukraine to raise money for children with diabetes, they both started crying. I broke down too. It was such an amazing coincidence and so humbling. They gave me the best massage of my life and shared their story of fleeing Ukraine at the start of the invasion.

Meanwhile, our team of organizers and social media volunteers were raising money and awareness. Paul’s partner Jayne was organizing fundraising events almost daily, raising £hundreds from afternoon tea’s to ice-skating events!

Approaching Auschwitz in Poland, we saw gloomy brick prison-like accommodation blocks. This was our first view of the concentration camp, and I immediately felt a lump in my throat as tears rolled down my cheeks. Many of my mother’s family had ended up there. The next morning, after Paul repaired his bike at a local shop, we toured Auschwitz. The experience was deeply moving, bringing home the need to fight for what you believe in – exactly what RideUkraine was about. What struck me most was how Putin’s invasion embodied Hitler’s ‘Lebensraum’ concept of expanding his empire to take lands he felt were rightfully his.

Our time in Southern Poland was enjoyable despite challenges. The cycle paths were amazing, the people welcoming, and the mood hugely positive. We met members of the Polish Diabetes Association, received gifts and medals of courage, and heard stories about volunteer groups that lined up at the border to welcome, feed and accommodate Ukrainian refugees.

Entering Ukraine

The day before entering Ukraine, tensions rose as we faced our final challenges in Poland. Paul’s rear luggage rack fell apart after hitting a culvert, and his continuing punctures were sapping his energy. A small incident – I accidentally spat while riding and it hit Paul – led to a big argument. By the time we reached our accommodation in Budomierz, he had stopped talking to me. I knew I had to intervene, or he might abandon the journey. I reminded him our ride wasn’t about us but about helping innocent children. Eventually he agreed, and we reconciled over dinner and drinks.

We left at 6:30am for the border crossing. After initially being told we couldn’t take bikes through that checkpoint, a border guard eventually took pity on us. The ride from the border to Lviv was one of the most terrifying experiences of my life. For five hours, we cycled along busy main roads in pouring rain with lorries roaring past, often forcing us off the road completely. Paul was attacked by two dogs, managing to fend them off. Along the roadside, we saw damaged vehicles, and ambulances whizzed past regularly.

We reached Lviv in darkness, where I fell off my bike for the first time when my wheels caught in a tram line. I bounced back up and grabbed my bike before it was crushed by a passing lorry. Several lorries had giant spikes attached to their wheel hubs – clearly designed as weapons against other vehicles. Everywhere around us was evidence of war – buildings badly damaged or destroyed by bombs and drone attacks.

Unable to access mobile networks, we were helped by a kind English-speaking woman we met in a supermarket. She walked with us 2km to our accommodation where we met Dougal Glaisher, another T1D athlete. He told us about the Ukrainians who want British right-hand drive cars. They put dummies on the left-hand side, so that Russian snipers hit the dummies. And we learned about the hundreds of thousands of IDPs (internally displaced persons) throughout Ukraine. The next day we joined a convoy of Siobhan’s Trust pizza trucks to an area on the outskirts of Lviv where many IDPs have been adopted by the community. This UK-created charity works with local community and church groups to provide food and to boost morale among the displaced Ukrainians. One story stuck with me, about a 14-year-old boy who escaped Mariupol with his cancer-stricken mother, only for her to die in surgery, leaving him orphaned.

I spoke to many Ukrainians in Lviv. One woman cried when she told me how much she was looking forward to seeing her husband next week. First time in a year. They have two children under 8 years old. Ukraine Soldiers get only 10 days a year to go home and see their families – usually that means three days to travel and one week at home.

Ukraine has one of highest rates of civilian casualties from landmines and unexploded ordnances in the world and ranks the highest for anti-vehicle mine incidents. As of April 2023, it was estimated that approximately 174,000 square kilometres of Ukrainian territory are contaminated by landmines. Now it is far greater, and it will take a generation to clear them.

Reaching Lviv was incredibly emotional. Though the hardest part of the journey still lay ahead, I felt a huge sense of accomplishment. Paul and I, despite our tensions, had worked as a genuine team.

Lviv to Kyiv

We spent four days in Lviv, recovering before our final push to Kyiv. We met with diabetes specialists who told us about the rapid increase in juvenile onset T1D, clearly stress-related. We did numerous interviews for Ukrainian media, and I spoke at the start of a big Ukrainian Diabetes Conference.

During our time in Lviv, we heard many stories about the war’s impact. The most compelling came from Alicia – the woman who guided us through the city on our first night. She and her family had sheltered in underground tunnels when Russians invaded Mykolaiv Oblast in Southern Ukraine. They lived underground for six months, surviving on bread, jam and rainwater. Many of their friends were captured, raped, tortured and murdered. Alicia said: “This war has brought out the best in some people and the worst in others… But this war united Ukrainians everywhere.”

We also met our guide Alex; a professional cyclist whose job was to get us safely to Kyiv. He knew the safe areas to cycle, where landmines had been laid, and importantly for Paul, also had a huge thirst for beer!

Our last day in Lviv concluded at the Diabetes conference, with moving speeches from both delegates and the Mayor of Lviv. He presented Paul and I with civilian medals of honour.

The journey to Kyiv was gruelling. We covered 185km and almost 1,000m of elevation on our first day out of Lviv, including off-road riding not suited to our skinny road tires. We practiced “drafting” – one person riding hard for 10 minutes, then the next taking their place in rotation. It’s efficient but requires intense focus, riding with wheels only inches from the person ahead at speeds up to 40 km/h.

The landscape was incredibly rural, with more horses and carts than cars. Everywhere we went, when we explained our mission, people gave us money for our cause – mostly €10 or less, but it meant so much. We witnessed a church funeral for a teenage local killed by a Russian bullet, another innocent life lost.

Each night we slept no more than 3 or 4 hours – the sound of drones and massive missile attacks keeping us all awake.

We stopped regularly each day to consume calories. Often it was local highway chains, but one time Alex took us to a beautifully styled American diner. I watched the female owner, sat alone, immersed in the hollow silence of her once-thriving, 1950s-themed restaurant. Its neon glow reflected off the dust-covered chrome fixtures and red vinyl, but now empty, booths. The jukebox silent, unused and unloved. Was she reflecting on happier times, before the twin storms of COVID and war had stolen the life from her dream. Or had she gone past the point of meaningless introspection?

I had to talk to her and reached out, asking about her life and trying to describe mine. I felt a synergy. Two lonely people in a world gone mad. She asked about our journey. How far had we come. Where were we going? I told her our story and she replied hesitantly in English – “I would like do that. Better than here…”

Our final day was the hardest yet – more than 190km of riding, with a final push through Kyiv’s hectic streets at night. We started at 7:30am on busy main roads in heavy traffic. After fast riding for three hours, we turned off to visit Andriivka, Borodianka, and Bucha – towns where Russians tried to break through to Kyiv at the start of the invasion. When they couldn’t penetrate and take Kyiv, they reduced these places to rubble, committing numerous war crimes against citizens – torture, rape, indiscriminate killings. In Bucha alone, 458 bodies were recovered, including nine children.

As we cycled on restricted roads, we passed warning signs of landmines and saw mine clearance personnel at work nearby. I passed a lone woman on the road and instinctively reached out to take her hand. The scenes of intense violence screamed out from the broken and destroyed houses around us. The woman’s eyes said everything – so much pain, so much sadness. I cycled on, sobbing, feeling totally inadequate.

Soon we were through Irpin and into Kyiv’s outskirts. We were joined by Denys from the Kyiv Randonneurs – long-distance cyclists who regularly ride over 200km just for exercise. Those final kilometres were the scariest, fastest, and wildest of our entire journey. Kyiv traffic is chaotic, but we moved quickly, crossing the famous bridge blown up by Ukrainians to stop the Russian advance, passing a Banksy graffiti memorial, and finally reaching University Square – the centre of Kyiv and the end of our journey.

We had done it! The cycling part of RideUkraine 2023 was finished, and so were we. Time for pizza and beers. Alex and Denys, still full of energy, cycled another 25km back to their homes afterward – nothing unusual for the tough Ukrainians.

We spent another four days in Kyiv doing presentations, visiting hospitals, inspiring children with T1D, and meeting government ministers. We spoke directly to the Minister of Health about the issues facing children with T1D – their vulnerability and how stress itself contributes to this autoimmune condition. Together with Dr. Vlasenko and many Ukrainian healthcare professionals, we raised awareness, united European diabetes communities, and brought hope to those sharing our chronic condition. In total, we raised more than $25,000 to buy much needed specialist T1D medication and equipment.

Bikepacking is not just physical but deeply emotional. Every day you experience highs and lows – for us it was equipment failures, meeting amazing people, mechanical issues, spontaneous invitations, hypoglycaemic attacks, unexpected vistas, destroyed buildings and landmines. It’s never boring and always incredibly real. Paul and I loved it all, and I encourage everyone to try it, even just for an overnight trip. Traveling by bicycle introduces you to a world you’ll never experience by car or public transport.

I will always remember the amazing Ukrainians we met – their strength, humour, beauty, courage, and resourcefulness in battling an enemy far larger than themselves. More than 85% of Ukrainians know friends, family, or colleagues who have died or been wounded fighting against the Russians. What struck me most were the everyday civilians – mothers, fathers, students, workers – who had dropped everything to defend their country. What a privilege to meet these brave people in their homeland. Bikepacking gave me this incredible experience, and I will be forever grateful.

Jerry’s website

jerrygore.com

An interview with Jerry about Bike Ukraine

youtube.com